Housing Policy Benchmarking: How Nigeria and the UK Tackle Urban Growth

A Comparative Study of Nigeria and the UK

As global urbanisation accelerates, the challenge of providing affordable, sustainable housing remains a central policy concern for both developed and emerging economies. A comparative assessment of the housing policies in the United Kingdom and Nigeria reveals stark contrasts in mortgage maturity, institutional frameworks, and the role of the state, while highlighting shared struggles regarding supply and affordability.

Institutional Frameworks and Mortgage Systems

The United Kingdom’s housing sector is built upon a highly sophisticated mortgage market and a long history of state intervention via social housing. The UK system is characterised by a diverse range of mortgage products, typically offering long-term tenures and competitive interest rates, supported by a robust credit scoring system. This allows a significant portion of the population to transition into homeownership through private financing.

In contrast, Nigeria’s housing policy is primarily driven by the National Housing Fund (NHF) and the Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN). Unlike the UK, Nigeria’s mortgage market remains at a nascent stage, hampered by high interest rates, short repayment periods, and a lack of integrated data for credit assessment. While the UK relies on a private market led approach with state safety nets, Nigeria’s system is largely public sector dependent, with commercial banks playing a limited role in long term residential lending.

Social Housing and Planning Regulations

The UK employs stringent planning regulations, such as Section 106 agreements, which mandate developers to include affordable units in large-scale commercial projects. This policy ensures that social housing is integrated into urban renewal. Furthermore, the UK’s "Right to Buy" scheme historically allowed council tenants to purchase their homes, though this has led to a significant depletion of public housing stock over the decades.

Nigeria’s approach to social housing has historically focused on direct government construction of housing estates. However, many of these projects face challenges such as poor maintenance, location mismatches, and abandonment. Nigeria’s Land Use Act of 1978 remains a significant bottleneck, as the difficulty in obtaining Certificates of Occupancy (C of O) creates tenure insecurity a hurdle largely absent in the UK’s well defined property rights system.

Addressing the Supply-Demand Gap

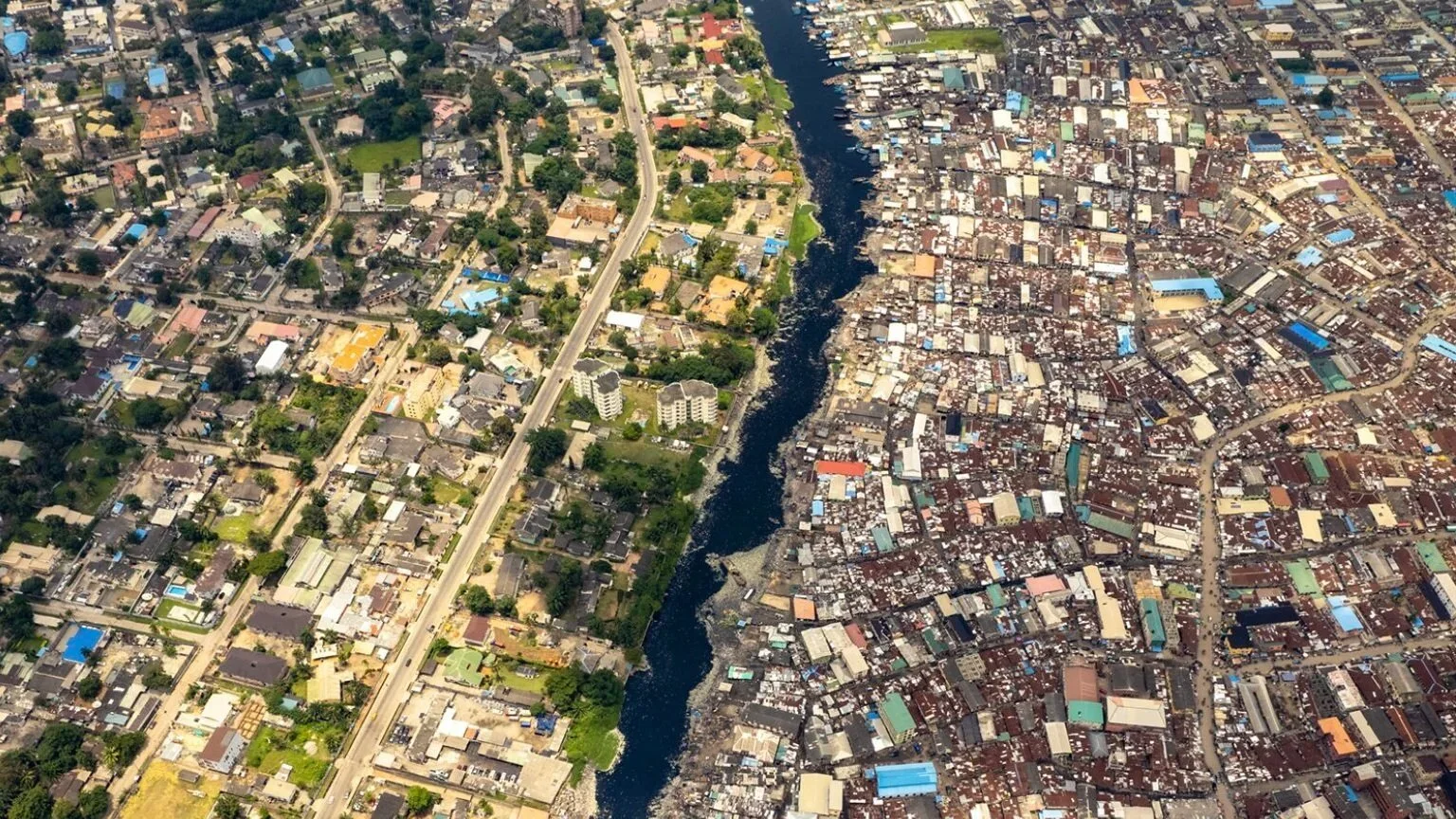

Both nations face acute housing shortages, albeit for different reasons:

The UK: The crisis is driven by high land costs, strict planning laws (Green Belt restrictions), and an aging population, leading to a "generation rent" phenomenon.

Nigeria: The deficit, estimated at over 28 million units, is fueled by rapid population growth, rural-to-urban migration, and the high cost of imported building materials.

According to data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) and Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the affordability ratio house price to income has widened in both countries, making homeownership an elusive goal for low-to-middle-income earners.

Strategic Lessons for Nigeria

Analysts suggest that Nigeria can adopt specific elements of the UK’s policy framework to improve its housing outlook. Key recommendations include:

Strengthening Foreclosure Laws: Adopting the UK's legal clarity regarding property recovery would encourage private banks to offer more mortgages.

Decentralising Land Administration: Reducing the bureaucracy associated with the Land Use Act to mirror the UK’s more fluid land registration system.

Incentivising Private Developers: Moving away from direct government construction and toward the UK model of mandated affordable housing quotas for private estates.

While the United Kingdom offers a blueprint for institutional stability and mortgage market maturity, Nigeria presents a landscape of massive untapped potential. The divergence in their housing policies reflects their unique socio economic histories; however, the universal need for reform in land management and financing remains clear. For Nigeria to bridge its housing gap, it must move beyond ad-hoc government projects and cultivate a market driven environment supported by the legislative transparency found in more mature economies.